quarta-feira, novembro 29, 2006

Constatações

Nelson Rodrigues

www.releituras.com

sexta-feira, novembro 03, 2006

segunda-feira, outubro 30, 2006

sexta-feira, outubro 06, 2006

Aguaviva

Manolo Díaz (compositor y productor)

José Antonio Muñoz (recitados)

Juan Carlos Ramírez (voz y guitarra)

José María Jiménez (voz y guitarra)

Rosa Sanz (voz)

Luís Gómez Escobar (voz)

Julio Seijas (guitarra)

Discografía:

1970 Cada vez más cerca

1971 Apocalipsis

1971 12 who sing the revolution

1971 Cosmonauta

1972 La casa de San Jamás

1975 Poetas andaluces de ahora

1977 No hay derecho

1979 La invasión de los bárbaros

sexta-feira, agosto 04, 2006

domingo, julho 30, 2006

terça-feira, julho 18, 2006

terça-feira, julho 04, 2006

quinta-feira, junho 01, 2006

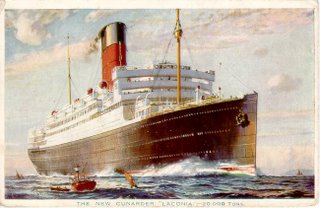

Histórias trágico marítimas - Laconia (1942)

Laconia

LaconiaLaconia was converted into an armed merchant cruiser in 1939, and then into a troopship in 1941. On September 12, 1942, she was torpedoed and sunk by U156, about 360 miles (575 km) north of Ascension. In all, out of 3,200 or more who were on board, less than 1000 survived.

As a result of the Laconia Incident, Doenitz ordered that no further rescues should be attempted by German U-boats. At Nuremberg, he was acquitted on a charge that the "Laconia order" was a war crime.

quarta-feira, maio 31, 2006

Histórias trágico marítimas - Laconia (1917)

by Floyd Gibbons

(Floyd's story appeared in newspapers throughout the United States.)

Queenstown, February 26, 1917

I have serious doubts whether this is a real story. I am not entirely certain that it is not all a dream. I feel that in a few minutes I may wake up back in stateroom B-19 on the promenade deck of the Cunarder Laconia and hear my cockney steward informing me with an abundance of "and sirs" that it is a fine morning.

It is now a little over thirty hours since I stood on the slanting decks of the big liner, listened to the lowering of the lifeboats, and heard the hiss of escaping steam and the roar of ascending rockets as they tore lurid rents in the black sky and cast their red glare over the roaring sea.

I am writing this within thirty minutes after stepping on the dock here in Queenstown from the British mine sweeper which picked up our open lifeboat after an eventful six hours of drifting and darkness and bailing and pulling on the oars and of straining aching eyes toward that empty, meaningless horizon in search of help.

But dream or fact, here it is:

The Cunard liner Laconia, 18,000 tons burden, carrying seventy-three passengers — men, women, and children — of whom six were American citizens — manned by a mixed crew of two hundred and sixteen, bound from New York to Liverpool, and loaded with foodstuffs, cotton, and war material, was torpedoed without warning by a German submarine last night off the Irish coast. The vessel sank in about forty minutes.

Two American citizens, mother and daughter, listed from Chicago, and former residents there, are among the dead. They were Mrs. Mary E. Hoy and Miss Elizabeth Hoy. I have talked with a seaman who was in the same lifeboat with the two Chicago women and he has told me that he saw their lifeless bodies washing out of the sinking lifeboat.

The American survivors are Mrs. F. E. Harris, of Philadelphia, who was the last woman to leave the Laconia; the Rev. Father Wareing, of St. Joseph's Seminary, Baltimore; Arthur T. Kirby, of New York, and myself.

A former Chicago woman, now the wife of a British subject, was among the survivors. She is Mrs. Henry George Boston, the daughter of Granger Farwell, of Lake Forest.

After leaving New York, passengers and crew had had three drills with the lifeboats. All were supplied with lifebelts and assigned to places in the twelve big lifeboats poised over the side from the davits of the top deck.

Submarines had been a chief part of the conversation during the entire trip, but the subject had been treated lightly, although all ordered precautions were strictly in force. After the first explanatory drill on the second day out from New York, from which we sailed on Saturday, February 17, the "abandon ship" signal — five quick blasts on the whistle — had summoned us twice to our lifebelts and heavy wraps, among which I included a flask and a flashlight, and to a roll call in front of our assigned boats on the top deck.

On Sunday we knew generally we were in the danger zone, though we did not know definitely where we were — or at least the passengers did not. In the afternoon during a short chat with Captain W. R. D. Irvine, the ship's commander, I had mentioned that I would like to see a chart and note our position on the ocean. He replied: "Oh, would you?" with a smiling, rising inflection that meant, "It is jolly well none of your business."

Prior to this my cheery early-morning steward had told us that we would make Liverpool by Monday night and I used this information in another question to the captain.

"When do we land?" I asked.

"I don't know," replied Capt. Irvine, but my steward told me later it would be Tuesday after dinner.

The first cabin passengers were gathered in the lounge Sunday evening, with the exception of the bridge fiends in the smoke-room.

"Poor Butterfly" was dying wearily on the talking machine and several couples were dancing.

About the tables in the smoke-room the conversation was limited to the announcement of bids and orders to the stewards. Before the fireplace was a little gathering which had been dubbed as the Hyde Park corner — an allusion I don't quite fully understand. This group had about exhausted available discussion when I projected a new bone of contention.

"What do you say are our chances of being torpedoed?" I asked.

"Well," drawled the deliberative Mr. Henry Chetham, a London solicitor, "I should say four thousand to one."

Lucien J. Jerome, of the British diplomatic service, returning with an Ecuadorian valet from South America, interjected: "Considering the zone and the class of this ship, I should put it down at two hundred and fifty to one that we don't meet a sub."

At this moment the ship gave a sudden lurch sideways and forward. There was a muffled noise like the slamming of some large door at a good distance away. The slightness of the shock and the meekness of the report compared with my imagination were disappointing. Every man in the room was on his feet in an instant.

"We're hit!" shouted Mr. Chetham.

"That's what we've been waiting for," said Mr. Jerome.

"What a lousy torpedo!" said Mr. Kirby in typical New Yorkese. "It must have been a fizzer."

I looked at my watch. It was 10:30 P.M.

Then came the five blasts on the whistle. We rushed down the corridor leading from the smoke-room at the stern to the lounge, which was amidships. We were running, but there was no panic. The occupants of the lounge were just leaving by the forward doors as we entered.

It was dark on the landing leading down to the promenade deck, where the first-class staterooms were located. My pocket flashlight, built like a fountain pen, came in handy on the landing.

We reached the promenade deck. I rushed into my stateroom, B-19, grabbed my overcoat and the water bottle and special life-preserver with which the Tribune had equipped me before sailing. Then I made my way to the upper deck on that same dark landing.

I saw the chief steward opening an electric switch box in the wall and turning on the switch. Instantly the boat decks were illuminated. That illumination saved lives.

The torpedo had hit us well astern on the starboard side and had missed the engines and the dynamos. I had not noticed the deck lights before. Throughout the voyage our decks had remained dark at night and all cabin portholes were clamped down and all windows covered with opaque paint.

The illumination of the upper deck on which I stood made the darkness of the water sixty feet below appear all the blacker when I peered over the edge at my station, boat No. 10.

Already the boat was loading up and men were busy with the ropes. I started to help near a davit that seemed to be giving trouble, but I was stoutly ordered to get out of the way and get into the boat.

We were on the port side, practically opposite the engine well. Up and down the deck passengers and crew were donning lifebelts, throwing on overcoats, and taking positions in the boats. There were a number of women, but only one appeared hysterical — little Miss Titsie Siklosi, a French-Polish actress, who was being cared for by her manager, Cedric P. Ivatt, appearing on the passenger list as from New York.

Steam began to hiss somewhere from the giant gray funnels that towered above. Suddenly there was a roaring swish as a rocket soared upward from the captain's bridge, leaving a comet's tail of fire. I watched it as it described a graceful arc in the black void overhead, and then, with an audible pop, it burst into a flare of brilliant white light.

There was a tilt to the deck. It was listing to starboard at just the angle that would make it necessary to reach for support to enable one to stand upright. In the meantime electric floodlights — large white enameled funnels containing clusters of bulbs — had been suspended from the promenade deck and illuminated the dark water that rose and fell on the slanting side of the ship.

"Lower away!" Someone gave the order and we started down with a jerk towards the seemingly hungry rising and falling swells.

Then we stopped with another jerk and remained suspended in mid-air while the man at the bow and the stern swore and tussled with the lowering ropes. The stern of the lifeboat was down, the bow up, leaving us at an angle of about forty-five degrees. We clung to the seats to save ourselves from falling out.

"Who's got a knife, a knife, a knife!" shouted a sweating seaman in the bow. "Great God, give him a knife!" bawled a half-dressed, jibbering Negro stoker, who wrung his hands in the stern.

A hatchet was thrust into my hand and I forwarded it to the bow. There was a flash of sparks as it crashed down on the holding pulley. One strand of rope parted and down plunged the bow, too quick for the stern man. We came to a jerky stop with the stern in the air and the bow down, but the stern managed to lower away until the dangerous angle was eliminated.

Then both tried to lower together. The list of the ship's side became greater, but, instead of our boat sliding down it like a toboggan, the taffrail caught and was held. As the lowering continued, the other side dropped down and we found ourselves clinging on at a new angle and looking straight down on the water.

A hand slipped into mine and a voice sounded huskily close to my ear. It was the little old German-Jew traveling man who was disliked in the smoke-room because he used to speak too certainly of things he was uncertain of and whose slightly Teutonic dialect made him as popular as smallpox with the British passengers.

"My boy, I can't see nutting," he said. "My glasses slipped and I am falling. Hold me, please."

I managed to reach out and join hands with another man on the other side of the old man and together we held him in. He hung heavily over our arms, grotesquely grasping all he had saved from his stateroom — a goldheaded cane and an extra hat.

Many hands and feet pushed the boat from the side of the ship and we sagged down again, this time smacking squarely on the pillowy top of a rising swell. It felt more solid than midair, at least. But we were far from being off. The pulleys twice stuck in their fastenings, bow and stern, and the one axe passed forward and back, and with it my flashlight, as the entangling ropes that held us to the sinking Laconia were cut away.

Some shout from that confusion of sound caused me to look up and I really did so with the fear that one of the nearby boats was being lowered upon us.

A man was jumping, as I presumed, with the intention of landing in the boat and I prepared to avoid the impact, but he passed beyond us and plunged into the water three feet from the edge of the boat. He bobbed to the surface immediately.

"It's Duggan!" shouted a man next to me.

I flashed the light on the ruddy, smiling face and water-plastered hair of the little Canadian, our fellow saloon passenger. We pulled him over the side. He sputtered out a mouthful of water and the first words he said were:

"I wonder if there is anything to that lighting three cigarettes off the same match? I was up above trying to loosen the rope to this boat. I loosened it and then got tangled up in it. The boat went down, but I was jerked up. I jumped for it."

His first reference concerned our deliberate tempting of fates early in the day when he, Kirby, and I lighted three cigarettes from the same match and Duggan told us that he had done the same thing many a time.

As we pulled away from the side of the ship, its ranking and receding terrace of lights stretched upward. The ship was slowly turning over. We were opposite that part occupied by the engine room. There was a tangle of oars, spars, and rigging on the seat and considerable confusion before four of the big sweeps could be manned on either side of the boat.

The jibbering, bullet-headed Negro was pulling directly behind me and I turned to quiet him as his frantic reaches with his oar were hitting me in the back. In the dull light from the upper decks I looked into his slanting face, eyes all whites and lips moving convulsively. Besides being frightened, the man was freezing in the thin cotton shirt that composed his entire upper covering. He would work feverishly to get warm.

"Get away from her; get away from her," he kept repeating. "When the water hits her hot boilers, she'll blow up, and there's just tons and tons of shrapnel in the hold!"

His excitement spread to other members of the crew in the boat. The ship's baker, designated by his pantry headgear, became a competing alarmist, and a white fireman, whose blasphemy was nothing short of profound, added to the confusion by cursing everyone.

It was the give-way of nerve tension. It was bedlam and nightmare.

Seeking to establish some authority in our boat, I made my way to the stern and there found an old, white-haired sea captain, a second-cabin passenger, with whom I had talked before. He was bound from Nova Scotia with codfish. His sailing schooner, the Secret, had broken in two, but he and his crew had been taken off by a tramp and taken back to New York. He had sailed from there on the Ryndam, which, after almost crossing the Atlantic, had turned back. The Laconia was his third attempt to get home. His name is Captain Dear.

"The rudder's gone, but I can steer with an oar," he said. "I will take charge, but my voice is gone. You'll have to shout the orders."

There was only one way to get the attention of the crew and that was by an overpowering blast of profanity. I did my best and was rewarded by silence while I made the announcement that in the absence of the ship's officer assigned to the boat, Captain Dear would take charge. There was no dissent and under the captain's orders the boat's head was held to the wind to prevent us from being swamped by the increasing swells.

We rested on our oars, with all eyes turned on the still-lighted Laconia. The torpedo had struck at 10:30 P.M. According to our ship's time, it was thirty minutes after that hour that another dull thud, which was accompanied by a noticeable drop in the hulk, told its story of the second torpedo that the submarine had dispatched through the engine room and the boat's vitals from a distance of 200 yards.

We watched silently during the next minute, as the tiers of lights dimmed slowly from white to yellow, then to red, and nothing was left but the murky mourning of the night, which hung over all like a pall.

A mean, cheese-colored crescent of a moon revealed one horn above a rag bundle of clouds low in the distance. A rim of blackness settled around our little world, relieved only by general leering stars in the zenith, and where the Laconia lights had shone there remained only the dim outline of a blacker hulk standing out above the water like a jagged headland, silhouetted against the overcast sky.

The ship sank rapidly at the stern until at last its nose stood straight in the air. Then it slid silently down and out of sight like a piece of disappearing scenery in a panorama spectacle.

Boat No. 3 stood closest to the ship and rocked about in a perilous sea of clashing spars and wreckage, As the boat's crew steadied its head into the wind, a black hulk, glistening wet and standing about eight feet above the surface of the water, approached slowly and came to a stop opposite the boat and not six feet from the side of it.

"Vot ship was dot?" the correct words in throaty English with the German accent came from the dark hulk, according to Chief Steward Ballyn's statement to me later.

"The Laconia," Ballyn answered.

"Vot?"

"The Laconia, Cunard line," responded the steward.

"Vot did she veigh?" was the next question from the submarine.

"Eighteen thousand tons."

"Any passengers?"

"Seventy-three," replied Ballyn, "men, women, and children, some of them in this boat. She had over two hundred in the crew."

"Did she carry cargo?"

"Yes."

"Vell, you'll be all right. The patrol will pick you up soon," and without further sound, save for the almost silent fixing of the conning tower lid, the submarine moved off.

"I thought it best to make my answers truthfuland satisfactory, sir," said Ballyn when he repeated the conversation to me word for word. "I was thinking of the women and children in the boat. I feared every minute that somebody in our boat might make a hostile move, fire a revolver, or throw something at the submarine. I feared the consequences of such an act."

There was no assurance of an early pickup, even though the promise was from a German source, for the rest of the boats, whose occupants — if they felt and spoke like those in my boat — were more than mildly anxious about our plight and the prospects of rescue.

We made preparations for the siege with the elements. The weather was a great factor. That black rim of clouds looked ominous. There was a good promise of rain. February has a reputation for nasty weather in the north Atlantic. The wind was cold and seemed to be rising. Our boat bobbed about like a cork on the swells, which fortunately were not choppy.

How much rougher weather could the boat stand? This question and the conditions were debated pro and con.

Had our rockets been seen? Did the first torpedo put the wireless out of business? Did anybody hear our S.O.S.? Was there enough food and drinking water in the boat to last?

That brought us to an inventory of our small craft, and after much difficulty we found a lamp, a can of powder flares, a tin of ship's biscuits, matches, and spare oil.

The lamp was lighted. Other lights were visible at small distances every time we mounted the crest of the swells. The boats remained quite close together at first. One boat came within sound and I recognized the Harry-Lauder-like voice of the second assistant purser, last heard on Wednesday at the ship's concert. There was singing, "I Want to Marry 'Arry," and "I Love to Be a Sailor."

Mrs. Boston was in that boat with her husband. She told me later that an attempt had been made to sing "Tipperary" and "Rule, Britannia," but the thought of that slinking dark hull of destruction that might have been a part of the immediate darkness resulted in an abandonment of the effort.

"Who's the officer in that boat?" came a cheery hail from a nearby light.

"What the hell is it to you?" bawled out our half-frozen Negro, for no reason imaginable other than, possibly, the relief of his feelings.

"Brain him with a pin, somebody!" yelled our profound oathsman, and accompanied the order with a warmth of language that must have relieved the Negro's chill.

The fear of some of the boats crashing together produced a general inclination toward further separation on the part of all the little units of survivors, with the result that soon the small craft stretched out for several miles, all of them endeavoring to keep their heads into the wind.

And then we saw the first light, the first sign of help coming, the first searching glow of white brilliance, deep down on the sombre sides of the black pot of night that hung over us. I don't know what direction that came from — none of us knew north from south — there was nothing but water and sky. But the light — it just came from over there where we pointed.

We nudged violently sick boat-mates and directed their gaze and aroused them to an appreciation of the sight that gave us new life.

It was over there — first a trembling quiver of silver against the blackness, then, drawing closer, it defined itself as a beckoning finger, although still too far away to see our feeble efforts to attract.

We nevertheless wasted valuable flares and the ship's baker, self-ordained custodian of biscuit tin, did the honors handsomely to the extent of a biscuit apiece to each of the twenty-three occupants in the boat.

"Pull starboard, sonnies," sang out old Captain Dear, his gray chin whiskers literally bristling with joy in the light of the round lantern which he held aloft.

We pulled lustily, forgetting the strain and pain of innards torn and racked from vain vomiting, oblivious of blistered hands and yet half-frozen feet.

Then a nodding of that finger of light — a happy, snapping, crapshooting finger that seemed to say "Come on, you men," like a dice player wooing the bones — led us to believe that our lights had been seen. This was the fact, for immediately the coming vessel flashed on its green and red sidelights and we saw it was headed for our position.

We floated off its stern for a while as it maneuvered for the best position in which it could take us on with the sea that was running higher and higher, it seemed to me.

"Come alongside port!" was megaphoned to us, and as fast as we could we swung under the stern and felt our way broadside toward the ship's side. A dozen flashlights blinked down to us and orders began to flow fast and thick.

When I look back on the night, I don't know which was the more hazardous — our descent from the Laconia or our ascent to our rescuer. One minute the swell lifted us almost level with the rail of the low-built patrol boat and mine sweeper; the next receding wave would carry us down into a gulf over which the ship's side glowed like a slimy, dripping cliff. A score of hands reached out, and we were suspended in the husky, tattooed arms of those doughty British jack tars, looking up into the weather-beaten, youthful faces, mumbling thanks and thankfulness, and reading in the gold lettering on their pancake hats the legend "H.M.S. Laburnum."

We had been six hours in the open boats, all of which began coming alongside one after another. Wet and bedraggled survivors were lifted aboard. Women and children first was the rule.

The scenes of reunion were heart-gripping. Men who had remained strangers to one another aboard the Laconia wrung each other by the hand, or embraced without shame the frail little wife of a Canadian chaplain who had found one of her missing children delivered up from another boat. She smothered the child with ravenous mother kisses while tears of joy streamed down her face.

Boat after boat came alongside. The waterlogged craft containing the captain came last. A rousing cheer went up as he landed his feet on the deck, one mangled hand hanging limp at his side.

The jack tars divested themselves of outerclothing and passed the garments over to the shivering members of the Laconia's crew.

The little officers' quarters down under the quarter-deck were turned over to the women and children. Two of the Laconia's stewardesses passed boiling basins of navy cocoa and aided in the disentanglement of wet and matted tresses.

The men grouped themselves near steam pipes in the petty officers' quarters or over the gratings of the engine rooms, where new life was to be had from the upward blasts of heated air that brought with them the smell of bilge water and oil and sulphur from the bowels of the vessel.

The injured — all minor cases, sprained backs, wrenched legs, or mashed hands — were put away in bunks under the care of the ship's doctor.

Dawn was melting the eastern ocean gray to pink when the task was finished.

In the officers' quarters, now invaded by the men, somebody happened to touch a key on the small wooden organ, and this was enough to send some callous seafaring fingers over the keys in a rhythm unquestionably religious and so irresistible under the circumstances that, although no one knew the words, the air was taken up in a serious humming chant by all in the room.

At the last note of the amen, little Father Wareing, his black garb snaggled in places and badly soiled, stood before the center table and lifted his head back until the morning light, filtering through the open hatch above him, shone down on his kindly, weary face. He recited the Lord's Prayer, all present joined, and the simple, impressive service ended as simply as it had begun.

Two minutes later I saw the old German-Jew traveling man limping about on one lame leg with a little boy in his arms, collecting big round British pennies for the youngster.

A survey and cruise of the nearby area revealed no more occupied boats and the mine sweeper, with its load of survivors numbering 267, steamed away to the east. A half an hour's steaming and the vessel stopped within hailing distance of two sister ships, towards one of which an open boat, manned by jackies, was pulling.

I saw the hysterical French-Polish actress, her hair wet and bedraggled, lifted out of the boat and handed up the companionway. Then a little boy, his fresh pink face and golden hair shining in the morning light, was passed upward, followed by some other survivors, numbering fourteen in all, who had been found half drowned and almost dead from exposure in a partially wrecked boat that was just sinking.

This was the boat in which Mrs. Hoy and her daughter lost their lives and in which Cedric P. Ivatt of New York, who was the manager for the actress, died. It has not been ascertained here whether Mr. Ivatt was an American or a British subject.

One of the survivors of this boat was Able Seaman Walley, who was transferred to the Laburnum.

"Our boat — No. 8 — was smashed in lowering," he said. "I was in the bow, Mrs. Hoy and her daughter were sitting toward the stern. The boat filled with water rapidly. It was no use trying to bail it out — there was a big hole in the side and it came in too fast. It just sunk to the water's edge and only stayed up on account of the tanks in it. It was completely awash. Every swell rode clear over us and we had to hold our breath until we came to the surface again. The cold water just takes the strength out of you.

"The women got weaker and weaker, then a wave came and washed both of them out of the boat. There were lifebelts on their bodies and they floated away, but I believe they were dead before they were washed overboard."

With such stories singing in our ears, with exchanges of experiences pathetic and humorous, we came steaming into Queenstown harbor shortly after ten o'clock tonight. We pulled up at a dock lined with waiting ambulances and khaki-clad men, who directed the survivors to the various hotels about the town, where they are being quartered.

The question being asked of the Americans on all sides is: "Is it the casus belli?"

American Consul Wesley Frost is forwarding all information to Washington with a speed and carefulness resulting from the experiences in handling twenty-five previous submarine disasters in which the United States has had an interest, especially in the survivors landed at this port.

His best figures on the Laconia sinking are: total survivors landed here, 267; landed at Bantry, 14; total on board, 294; missing, 13.

The latest information from Bantry, the only other port at which survivors were known to have landed, confirms the report of the death of Mrs. Hoy and her daughter.

Luiz Pacheco

É um bicho poderoso, este, uma massa animal tentacular e voraz, adormecida agora, lançando em redor as suas pernas e braços, como um polvo, digo: um polvo excêntrico, sem cabeça central, sem ordenação certa (natural); um grande corpo disforme, respirando por várias bocas, repousando (abandonado) e dormindo, suspirando, gemendo. Choramingando, às vezes. Não está todo à vista, mas metido nas roupas, ou furando aos bocados fora delas. Parece (acho eu, parece) uma explosão que atingiu um grupo de gente parada e, agora, o que está ali são restos de corpos mutilados : uma pernita de criança, um braço nu sòzinho, um punho fechado (um adeus?... uma ameaça?...), um tronco mal coberto por uma camisa branca amarrotada. Ou seria, então, talvez, um desabamento súbito, uma avalanche de neve encardida, que nos cobriu a todos, ao acaso, aos bocados, e para ali ficámos, quietos e palpitando, à espera, quietos e confiantes, dum socorro improvável, cada vez mais (e as horas passam!) improvável, incerto, aguardando a luz da manhã, que chega sempre, que acaba sempre por chegar, para vivos e mortos, calados ou palrantes, ladinos ou soterrados, os que já desistiram da madrugada e os que, ainda, contra qualquer lógica, contra qualquer quantidade de esperança, confiam ainda e esperam.

(...)

Desde que estamos aqui, estudámos, experimentámos várias posições para nos ajeitarmos a dormir melhor: ora todos em fileira, ao lado uns dos outros, para a cabeceira da cama, ora distribuídos como agora, três para cima, dois para baixo, ou, então, com um dos miúdos (a Lina ou o Zé) atravessados a nossos pés. E havia, ainda, o problema da colocação ou das vizinhanças: eu e a Irene num lado e os miúdos noutro, ou nós no meio e eles um de cada lado, isto com insucessos, preferências, trambolhões cama abaixo, muitos pontapés, mijas, rixas, complicações de família, favoritismos e cìumeiras e choros e berraria às vezes, resolvidos em família entre risos e lágrimas, bofetões, beijos; descomposturas, carícias leves... Também na cama as posições variavam conforme o frio ou o calor, conforme, principalmente, o frio ou o calor que fazia na cama, pois os cobertores, às vezes, eram convocados (um, ou dois) à pressa, num afã de salvação pública (nossa) e seguiam com destino incerto. Depois, não havia trapada pelas gavetas que chegasse para os substituir, e até jornais, são óptimos, ramalham duma maneira estranha, apreciada pelos vagabundos que têm sono e frio. A verdade é esta: o frio não entrava connosco!

Somos gente pura: os mais novos não sabem o que é a promiscuidade, a minha rapariga se vir a palavra escrita deve achá-la muito comprida e custosa de soletrar: pro-mis-cu-i-da-de (pelo método João de Deus, em tipos normandos e cinzentos às risquinhas, até faz mal à vista!). A promiscuidade: eu gosto. Porque me cheira a calor humano, me sobe em gosto de carne à boca, rne penetra e tranquiliza, me lembra - e por que não ?! - coisas muito importantes (para mim, libertino se o permitem) como mamas, barrigas, pele, virilhas, axilas, umbigos como conchas, orelhas e seu tenro trincar, suor, óleos do corpo, trepidações de bicharada. E a confusão dos corpos, quando se devoram presos pelos sexos e as bocas. E as mãos, que agarram e as pernas, que enlaçam. Máquinas que nós somos, máquinas quase perfeitas a bem dizer maravilhosas, inda que frágeis, como não admirar as nossas peças, molas e válvulas e veias, todas elas animadas por um sopro que lhes parece alheio mas sai do seu próprio movimento, do arfar, dos uivos do animal, do desespero do anjo caído. E a par disso que é o trivial, que é o que cada um, tosco ou aleijado tem para dar e trocar, fatalidades, na sua mísera ou portentosa condição de bicho, a beleza, que é a surpresa, a harmonia das formas, que é a excepção e a inteligência, que é a reminiscência dos deuses. Ao lado do bicho, natural e informe, a estátua - onde a carne se afeiçoou em linhas puras, sabe-se lá porquê, por quem e para que fim (sim, o fim sabemos e é o que irmana todos na caveira desdentada horrível a rir-se muito da beleza e dos olhos que a gozavam, da estátua viva e das mãos que a percorriam demoradamente, enlevadas). A curva flutuante de um seio de donzela, a provocação que é a anca do efebo ou da ninfa, tão parecidas que se confundem; a amplidão do olhar e os seus mistérios, esquivas e trocadilhos - íntima largueza do reino da alma que jamais encontrarás seu fundo, e a cor alacre arrebatada duma risada; os passos, o cetim da pele, o emaranhado dos pêlos do púbis, e a alegria loira duma cabeleira solta, desmanchada nos abraços, saindo triunfal duma cama semidesfeita. A persuasão da fala, a fenda estreita que é a porta do paraíso e as outras mil maneiras ,de ver e gostar de ver um corpo ser nosso, subjugado por uma técnica ou o seu próprio desejo dissoluto; e tudo assoprado por dentro, tudo recheado de novas grutas ainda por explorar e que também jamais as conhecerás ou iluminarás todas, se elas a si mesmas se ignoram. Tudo cativado por uma divindade que é o todo, que é o Corpo, em risos e gritos, balbuceios de orgasmo e ranger de dentes; e a solidão duma lágrima lenta que desce a face no silêncio e na amargura; e o resfolegar do moribundo que já nada quer dos homens e com os homens, mas ostenta ainda na severidade da máscara, no desdém da boca desgarrada, uma altaneira nobreza; e a ferida do teu sexo aberta como uma nova última esperança de recomeçar tudo desde o princípio como se fora a primeira vez a fuga para o sono e o sonho. Nem eu me atrevia a falar-vos disto, senhores; nem eu nunca me atreveria a repetir coisas tão velhas, se não as visse serem atiradas para trás das costas, como se a enterrar em vida o corpo em cálculos e tristura os homens fossem mais livres e mais humanos. Ódio ao corpo, andam esses a dizer há dois mil anos, como se neste curto lapso de tempo da história do homem só devesse haver fantasmas descarnados. Ódio ao corpo, o teu e o meu, disfarçado em tarefas vis e loas absurdas, cobardias pequeninas. Nada disso é gente e eu gosto de estar com gente (falo de corpos), um enchimento de gente à roda, compacta, onde recebemos e damos, estamos e lutamos, sofremos em comum e gozamos. Onde tudo de nós é ampliado, revigorado, e medido pelo colectivo, pelos outros - espelho e limite, cadeia e espaço imenso, liberdade e nossa conquista.

Cá em casa a nossa cama é a nossa liberdade imediata. Tem os nomes que quiserem. É a cama do pai de família, austero e mandão, ou do dorminhoco pesado quando regressa embriagado para casa. É a cama do libertino. É o leito (suponhamos!) Luís-Qualquer-Coisa, XV ou XVI, do milionário, porque nela somos reis e milionários de ternura e de abraços, de palavras ciciadas; e é o catre sem lençóis, fracas mantas, e mau cheiro, do maltês que não sabe para onde o destino o manda (e somos isto, e que de longes terras viemos! quantos naufrágios! quanta coisa fomos largando para facilitar a marcha até aqui!), a enxerga do pedinte (e nós o somos também: porque temos falta de tudo e porque acordamos de manhã sem uma bucha de pão para dar às crianças e sem saber ainda onde o ir buscar). Podia ser (dava para) um bom título de uma comédia picante, bulevardesca; UMA CAMA PARA CINCO; idem para um filme neo-realista, onde nem cama houvesse, só umas palhas podres e mijadas, com gaibéus ensonados, embrutecidos do calor e do vinho, fedor de pés, talvez um harmónio desafiando as cigarras e os grilos na cálida noite da planície alentejana. Uma cama para cinco, em herança, constituía um demorado caso de partilhas. Nós dormimos. As vezes, muitas vezes, beijos e abraços.

Em toda a cidade que dorme e respira, eu luto com a dispneia e escrevo. Em toda a cidade que repousa e se esquece, na Avenida dos Combatentes eu debato-me contra a morte e escrevo diante da minha pequena tribo que dorme. A tribo dorme: a Lina mostra um punho fechado (ideias avançadas terá a mocinha?); o rapaz está de costas e quase destapado (parece um Cupido cansado; na larga queixada, porém, uma expressão terrena, máscula - a cara camponesa e rude do avô Matias); o bebé ressona ou balbucia qualquer uma esperança que só ele entende. Ela, a Irene, a minha pequena deusa de tranças loiras, encosta-se a mim e calada cálida repousa cansada. Sou um deus grego ! Fauno serôdio, Pan sem flauta, Orfeu decaído de quantas desilusões e frios cinismos, um Vulcano cornudo às ordens de Vocências, do meu espaldar senhorial contemplo o rebanho provisório que inventei, patriarca e profeta do meu próprio futuro. E receio, oh como receio, que os deuses a valer me castiguem! E desejo, oh como desejo, que chegue a manhã e eu esteja respirando ainda pelos foles dos pulmões que o enfizema vai dilatando minguando a elasticidade; que o meu coração eia! sus! bata ainda quando, num quintal que não sei, perto, o galo canta.

Quando a dor no peito me oprime, corre o ombro, o braço esquerdo, surge nas costas, tumifica a carótida e dá-lhe um calor que não gosto; quando a respiração se acelera em busca duma lufada que a renasça, o medo da morte afinal se escancara (medo-mor, tamanha injustiça, torpeza infinita), aperto a mão da Irene, a sua mão débil e branca. Quero acordá-la. E digo : «não me deixes morrer, não deixes...» Penso para comigo, repito para me convencer: «esta pequena mão, âncora de carne em vida, estas amarras suas veias artérias palpitantes, este peso dum corpo e este calor, não me deixarão partir ainda...» E aperto-lhe a mão com força, e acabo às vezes por adormecer assim, quase confiante, agarrado à sua vida. Ah, são as mulheres que nos prendem à terra, a velha terra-mãe, eu sei, eu sei ! São elas que nos salvam do silêncio implacável, do esquecimento definitivo, elas que nos transportam ao futuro, à imortalidade na espécie (nem teremos outra) pelo fruto bendito do seu ventre (eu sei, eu sei...)

("Comunidade", Contraponto, 1964)

ver mais aqui: http://www.triplov.com/luiz_pacheco/index.html

terça-feira, maio 30, 2006

Nana Mouskouri

Ioana Mouskouri (Joanna in English; nicknamed "Nana" from a young age) was born October 13, 1934, on the island of Crete, in the town of Chania (or Carée in French). Her father worked as a movie projectionist, and moved the family to Athens when she was three. Much of her childhood was colored by the Nazi occupation of Greece -- during which time her father worked for the resistance movement -- and the four-year civil war that broke out on the heels of World War II. She started taking singing lessons at age 12, and listened regularly to radio broadcasts of American jazz singers (Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, and Billie Holiday in particular) and French chansonEdith Piaf, etc.). In 1950, Mouskouri was accepted into the Athens Conservatory, where she studied classical music with an emphasis on singing opera. In 1957, it was discovered that Mouskouri had been singing with a jazz group by night, and she was summarily kicked out of the Conservatory. stars (

Mouskouri began singing jazz in nightclubs, concentrating especially on Ella Fitzgerald repertory. In 1958, she met the emerging songwriter Manos Hadjidakis, who would become her mentor in the field of popular music, and recorded an EP featuring four of his compositions for a small record label that year. The following year she performed his "Kapou Iparchi Agapi Mou" (co-written with poet Nikos Gatsos) at the inaugural Greek Song Festival; it won first prize, and Mouskouri's high-profile performance began to make a name for her. At the 1960 festival, she performed two more Hadjidakis compositions, "Timoria" and "Kiparissaki," which tied for first prize; not long after, she made her first appearance outside of Greece at the Mediterranean Song Festival, held in Barcelona. She performed the Kostas Yannidis composition "Xypna Agapi Mou," which again won first prize, and attracted interest from several international record companies. She wound up signing with the Paris-based Philips-Fontana axis.

In 1961, Mouskouri sang on the soundtrack of a German documentary about Greece, which resulted in the German-language single "Weisse Rosen aus Athen" ("The White Rose of Athens"). Adapted from a folk melody by Manos Hadjidakis, it was an enormous hit, selling over a million copies in Germany; later translated into several different languages, it went on to become one of her signature tunes. In 1962, she met producer Quincy Jones, who flew her to New York to record an album of American standards titled The Girl From Greece Sings; not long after, she had a sizable U.K. hit with the pop standard "My Colouring Book." In 1963, she settled permanently in Paris and recorded a Greek-language album; she also sang Luxembourg's entry in the Eurovision Song Contest that year, "À Force de Prier," which became an international hit, and helped win her the prestigious Grand Prix du Disque in France. She attracted the notice of composer Michel Legrand, who supplied her with two major French hits in "Les Parapluies de Cherbourg" (1964) and "L'Enfant au Tambour" (1965). Also in 1965, she recorded her second English-language album in America, Nana Sings, and found a patron in Harry Belafonte, who brought her on tour with him through 1966, and teamed with her for the live duo album An Evening With Belafonte/Mouskouri.

Mouskouri ascended to superstardom in France with her 1967 album Le Jour Où la Colombe, which featured much of the core of her French repertoire: "Au Coeur de Septembre," "Adieu Angélina," "Robe Bleue, Robe Blanche," and a cover of the French pop classic "Le Temps des Cerises," among others. Also scoring with a version of "Guantanamera," she made her first headlining appearance at Paris' legendary Olympia concert theater that year, with a repertoire blending French pop, Greek folk, and Manos Hadjidakis numbers. The following year, she turned her attention to the British market, hosting a variety series called Nana and Guests; in 1969, she released her first full-length British LP, Over and Over, a smash hit that spent almost two years on the charts. Already maintaining a heavy international touring schedule in the late '60s, MouskouriBizet's opera Carmen, in tandem with Serge Lama. Elsewhere, her 1975 album Sieben Schwarze Rosen was a significant success in Germany, and her English-language album Book of Songs sold millions of copies worldwide. spent much of the '70s on the road, broadening her worldwide popularity to levels rarely equaled. In France, she released a series of top-selling albums that included Comme un Soleil, Une Voix Qui Vient du Coeur, Vielles Chansons de France, and Quand Tu Chantes, among others; she also recorded a successful version of "Habanera," from

Mouskouri had another English-language triumph with 1979's Roses and Sunshine, which was particularly popular in Canada. She scored a worldwide hit with 1981's "Je Chante Avec Toi, Liberté," which was translated into several languages after its widespread success in France, and also helped boost her hit German album Meine Lieder Sind Meine Liebe. In 1984, MouskouriMouskouri recorded "Only Love," the theme song to a BBC TV series that went on to top the U.K. charts; it was also a hit in the French translation "L'Amour en Héritage." That same year, Mouskouri made a play for the Spanish-language market with the hit single "Con Todo el Alma," a major success in Spain, Argentina, and Chile. She released five albums in different languages in 1987, and the following year returned to her classical conservatory roots with the double LP The Classical Nana (aka Nana Classique), which featured some of her favorite opera excerpts. returned to Greece for her first live performance in her homeland since 1962; from then on, she would record Greek-language albums for her home market. In 1986,

domingo, maio 28, 2006

Robert Michael Ballantyne - A Ilha de Coral

Robert Michael Ballantyne

(1825-1894)

A Short Biography

One generally reads a book, especially a famous book, with greater interest when one knows something of the personal history and the character of the writer. There are, however, exceptions to the rule. There are writers whose life-story is best told not in, but by their books; and R.M. Ballantyne was one of these. Many schoolboys will be content to know him simply as the man who wrote their favourite books – Hudson Bay, The Coral Island, Martin Rattler, and a score or two more; but even these will appreciate his work more highly when they know how much of conscientious devotion and how much of labour and personal risk were involved in his method of doing it. It is in this sense that Ballantyne’s stories are to a large extent autobiographical, and it is in this sense that he deserves the title of “Ballantyne the Brave” affectionately given him by his successor as a writer for boys, R.L. Stevenson.

Robert Michael Ballantyne was born at Edinburgh, April 24, 1825. His father, Alexander Ballantyne, was brother and junior partner of John and James Ballantyne, the printers and friends of Sir Walter Scott. His mother was Randall Scott Grant, daughter of a Dr. Grant of Inverness. Of his boyhood there is not much to tell. His sister, Randall Ballantyne, who possessed a good deal of literary ability, used to speak of him as a bright and clever boy, not much given to hard study, but fond of reading and of story-telling, with a decided turn for adventure and romance; always affectionate and upright. He attended the Edinburgh Academy for some time; but his regular schooling was meagre, and one of the regrets of his life was that he had made so little use of his opportunities in this respect, such as they were. The ease and fluency with which he wrote were mainly the result of practice, and they increased as his years advanced.

While Ballantyne was still a boy, the family circumstances made it necessary that he should begin the battle of life on his own account. He tells us in his Personal Reminiscences that his father was one day reading in the newspapers an account of the exploration of the north coast of America by Messrs. Dease and Simpson. Dropping his paper and looking over his spectacles, he said to his son,—

“How would you like to go into the service of the Hudson Bay Company, and discover the North-West Passage?” Dease and Simpson were officers of the Company when they made their discoveries.

“All right, father,” said the boy – or words indicating acquiescence. It happened that a relative of the family held a high post in the Company’s service, and through him young Ballantyne obtained a clerkship under the Company with a salary of £20 a year. He sailed for Hudson Bay in 1841, when he was sixteen years of age. The appointment was in all respects a fortunate one. The country and the life suited his adventurous disposition, and were the means besides of developing a literary faculty of which he had previously been unconscious. In fact, his sojourn in the wilds of North America was what made him a story-teller and a writer of books for boys.

It is unnecessary to describe with any detail the events of the six years spent in the Hudson Bay Territory. Ballantyne has himself told the story of that time in his own charming way in Hudson Bay. He sailed from Gravesend in June 1841 in the Prince Rupert, one of the sailing ships of the Company, and after a rough and stormy voyage he landed at York Factory in August. The posts at which most of his time was spent were York Factory, where he remained for two years at a stretch; Norway House, near the north end of Lake Winnipeg; Fort Garry, in the Red River Settlement (now Manitoba); Tadousac, at the mouth of the Saguenay River; and Seven Islands, on the Gulf of St. Lawrence. He sailed from New York for England in May 1847, almost exactly six years after his departure from Gravesend.

Ballantyne himself described his Hudson Bay life as “a hard, rough, healthy life.” He and his comrades spent most of their time in trading in furs with the Red Indians. A little office-work had to be done, but much more of canoeing, boating, fishing, shooting, and, he adds, “wishing, and skylarking. It was a ‘jolly’ life, no doubt, while it lasted, but not elevating.”

How then did it make him an author? The answer is found in the necessity he felt to adopt some occupation to relieve the loneliness of existence. In those days they had a mail only twice in the year – one in summer by the Company’s ship, and one in winter through the trackless wilderness by sledge and snow-shoe. With a winter of eight months’ duration, and a temperature often of 50 below zero, time was apt to hang heavily on his hands. With a view to lighten it a little, he wrote long letters to his mother in Scotland – necessarily long because of the interval between the mails. Whenever he felt a touch of home-sickness, he got out his sheets of “imperial” paper and “entered into spiritual intercourse with ‘home.’ To this long-letter writing,” he adds, “I attribute whatever small amount of facility in composition I may have acquired.”

These letters, however, did not form his book. The idea of a regular and continuous narrative did not occur to him until near the end of his stay in Canada. During the wearisome months he spent at Seven Islands, on the Gulf of St. Lawrence, in 1846, with no companion but his French-Canadian “man Friday” and factotum, and no neighbour nearer than within seventy or eighty miles, he was desperately lonely. He had no books, or newspapers, or magazines, or literature of any kind; no game to shoot, and no boat to fish from. “But I had pen and ink, and, by great good fortune, was in possession of a blank-paper book fully an inch thick.” He knew that his mother would read any amount of his outpourings, and he wrote without stint. Even then he had no idea that his manuscript would ever become a printed book. “It was merely a free-and-easy record of personal adventure and everyday life, written, like all else that I penned, solely for the uncritical eye of that long-suffering and too indulgent mother.”

After he had been at home for two or three years, the manuscript book was handed round among relatives and privileged friends. It came under the eye of “a printer-cousin,” who offered to print it, and ere long Hudson Bay was published by the Blackwoods, was praised by the press, and turned out a distinct success commercially (1850).

His literary consciousness, however, was not yet awakened. He looked on himself as a business man, and accepted a partnership in the firm of Thomas Constable and Co., printers in Edinburgh. After the publication of Hudson Bay he allowed several years to pass without putting pen to paper in the way of literary effort. Even then the effort was not spontaneous: it was the result of a suggestion from the outside. The late Mr. William Nelson had been impressed with the interesting character of Hudson Bay, and with the undoubted literary power it revealed. Happening to meet Ballantyne in 1854, he asked him how he would like the idea of taking to literature as a profession. Ballantyne was taken by surprise, and answered vaguely; but when the suggestion was promptly followed by “an order” for a story, he agreed to make trial, and the result was The Young Fur-Traders – Ballantyne’s first story-book for young folks, published by Thomas Nelson and Sons in 1855. The rest of his life was spent in writing similar books, at the rate of one or two a year. He estimated that, besides occasional articles, he had written “something like eighty complete stories.”

In everything he undertook, Ballantyne was actuated by earnestness of purpose. When he resolved to become a literary man, he made literature his business; but it was a business in which he took the greatest interest, and from which he derived real enjoyment. He settled down quietly, when about thirty years of age, to the busy life of a story-teller in his house at Millerfield Place, near the Meadows, on the south side of Edinburgh. Besides his regular production of works of fiction, he contributed occasional articles to magazines and newspapers. He was also an accomplished draughtsman, and he painted cleverly in water-colours. Though only an amateur with the brush, his pictures were on several occasions hung on the walls of the Royal Scottish Academy beside those of professional artists.

In his earliest stories, The Young Fur-Traders and Ungava; a Tale of Eskimo Life, he drew upon his own experiences in North America. When that material was exhausted, and he had to resort to fresh fields, he relied partly on authentic books of travel, but more on personal visits to the scenes described. To indicate the kind of books from which he derived information, mention may be made of Ellis’s “Polynesian Researches,” Olmsted’s “Journey through Texas,” Scoresby’s “Arctic Regions,” Kane’s “Arctic Regions,” and Greely’s “Arctic Service.” He was always on the watch for travellers who could give him first-hand information. Much of the material for Ungava was got from an old retired “Nor’-wester” who had lived long in Rupert’s Land. He obtained information which he used in Blue Lights; or, Hot Work In the Soudan, from Miss Robinson, the soldier’s friend.

Few writers of fiction have been so exact or so conscientious as he was regarding his facts. He made occasional mistakes. He tells with gusto how he blundered in The Coral Island regarding cocoa-nuts, which he described as growing on the trees without the outer fibrous case, and how months or years passed before any one drew his attention to the error. Considering the number of his books and the wide area of the world they cover, the severest criticism admits that his slips were trifling and remarkably rare. One charge to which he was never fairly liable, and about which he was rather sensitive when it was even hinted, was that of “drawing the longbow.” He said that he “had always laboured to be true to fact and to nature, even in my wildest flights of fancy.” Testimonies to his accuracy have not been wanting. With reference to an exciting incident in Blue Lights, a certain colonel wrote to him to say that it was his son who had commanded the gallant band that performed the exploit.

The amount of trouble he took in order to secure that kind of realism was extraordinary. Before he wrote The Lifeboat, he went to Ramsgate and spent some time there in close friendship and alliance with the coxswain of the Ramsgate boat. The information for The Lighthouse he gathered during a residence on the Bell Rock Lighthouse for three weeks as the guest of the keepers. To understand The Floating Light, he spent a fortnight aboard the Gull lightship, off the Goodwin Sands, and he wrote in The Scotsman (March 26, 1870) a graphic account of his visit, which attracted a great deal of notice. To gain the knowledge requisite for writing In the Track of the Troops, he spent some weeks with the commander of H.M.S. Thunderer on board of his ship. As a preparation for Fighting the Flames, he obtained permission to join the Salvage Corps of the London Fire Brigade; and he donned the uniform of the corps, and went careering through the streets of London on fire-engines.

For most of his other books he adopted a similar plan, and even took long journeys and voyages to obtain accurate information, and local colouring and feeling. Thus Deep Down took him to Cornwall; Erling the Bold, to Norway; The Pirate City, to Algiers; The Settler and the Savage, to the Cape; The Young Trawler, to the North Sea fishing-ground.

As a further means of ensuring accuracy in details, he was careful to submit his proof-sheets to experts when that was possible. Thus the proofs of Fighting the Flames were gone over by the late Captain Shaw, the head of the London Fire Brigade, and those of Post Haste by Sir Arthur Blackwood, Secretary to the General Post Office, St. Martin’s-le-Grand.

Apart from the general purpose of all his books – namely, to describe adventures, and to convey information in a pleasant way – many of them were written in support of definite causes and institutions. Thus The Lifeboat was intended to enlist the sympathy of young folk with the work of the “Royal National Lifeboat Institution.” In acknowledgment of his valuable service, the Institution presented him with a beautiful model of a lifeboat, which stood in a glass case in his study, and of which he was very proud. In the Track of the Troops was written to discredit war, though some hasty critics condemned it as having the opposite tendency. Dusty Diamonds was based on the work of Miss Macpherson and Dr. Barnardo in the slums of the East of London. The Young Trawler deals almost entirely with the religious mission to the North Sea fishermen.

His stories are books of incident rather than books of character. The personalities in them were not finished portraits: they were rather boldly-outlined sketches; but as far as they went they were consistent and clearly defined. All his books are characterised by a pure and healthy tone. He wrote no line that he or any one else could desire to blot.

Himself an earnestly religious man, Ballantyne was never ashamed of the religious tone that appeared in many of his books. He knew well that some persons thought there was too much of religion in his stories, while others thought there was too little. Believing that it was impossible to please every one in this matter, his rule was to satisfy his own conscience and to exercise his own judgment. “When I write,” he said, “on a subject which has religion for a basis, I must not let the feelings of worldly people destroy the religion in my books.” (From “How I write Boys’ Books.” — The Quiver, April 1893.)

He was a most industrious writer, and he did not restrict himself to certain hours. He generally began work soon after breakfast, and he worked on as long as he felt inclined to continue. He confessed that he often worked too long at a stretch, and that he did not take enough of exercise. Though not endowed by nature with a very robust constitution, he enjoyed fairly good health during the greater part of a pretty long life. He worked steadily as long as his work lasted, and he did not object to solitude. Sometimes he retired with his materials to a lonely village where he was unknown, and remained there till his book was finished.

Ballantyne was not very fastidious in matters of style. His language was well chosen, and he wrote easily and with directness; but he did not profess to be a stylist, and he never indulged in fine writing. He seldom re-wrote what he had written, and while he revised carefully he polished or “dressed” his style very little. His English is always simple and business-like.

In 1866 Ballantyne married Miss Jane Dickson Grant, daughter of the Rev. William Grant, minister of the parish of Cavers, Roxburghshire. Their family consisted of three sons and three daughters, all of whom survived their father. One of the sons became a tea-planter in India, another a soldier, and a third a sailor.

Ballantyne continued to live in Edinburgh till 1873, and after sojourning temporarily in London and elsewhere, he settled down at Harrow-on-the-hill in 1878, and there he remained till the end of his life.

He died at Rome, on February 8, 1894. Having been in feeble health for some time, he had accepted an invitation to spend the winter with friends at Tivoli; and he died on the homeward way.

He was buried in the English cemetery at Rome, and a few months later, friends at home placed a white marble monument over his grave, bearing the following inscription:—

In Loving Memory Of

Robert Michael Ballantyne,

The Boys’ Story-Writer,

Born At Edinburgh, April 24, 1825 – Died At Rome,

February 8, 1894.

This Stone Is Erected By Four Generations Of

Grateful Friends In Scotland And England.

“His Servants shall serve him,

and they shall see his face.”

http://www.athelstane.co.uk/ballanty/index.htm

Emile Zola

Emile Zola was born in Paris. His father, François Zola, was an Italian engineer, who acquired French citizenship. Zola spent his childhood in Aix-en-Provence, southeast France, where the family moved in 1843. When Zola was seven, his father died, leaving the family with money problems - Emilie Aubert, his mother, was largely dependent on a tiny pension. In 1858 Zola moved with her to Paris. In his youth he became friends with the painter Paul Cézanne and started to write under the influence of the romantics. Zola's widowed mother had planned a career in law for him. Zola, however, failed his baccalaureate examination - as later did the writer Anatole France, who failed several times but finally passed. According to one story, Zola was sometimes so broke that he ate sparrows that he trapped on his window sill.

Before his breakthrough as a writer, Zola worked as a clerk in a shipping firm and then in the sales department of the publishing house of Louis-Christophe-Francois-Hachette. He also wrote literary columns and art reviews for the Cartier de Villemessant's newspapers. As a political journalist Zola did not hide his antipathy toward the French Emperor Napoleon III, who used the Second Republic as a springboard to become Emperor.

During his formative years Zola wrote several short stories and essays, 4 plays and 3 novels. Among his early books was CONTES Á NINON, which was published in 1864. When his sordid autobiographical novel LA CONFESSION DE CLAUDE (1865) was published and attracted the attention of the police, Zola was fired from Hachette.

After his first major novel, THÉRÈSE RAQUIN (1867), Zola started the long series called Les Rougon Macquart, the natural and social history of a family under the Second Empire. "I want to portray, at the outset of a century of liberty and truth, a family that cannot restrain itself in its rush to possess all the good things that progress is making available and is derailed by its own momentum, the fatal convulsions that accompany the birth of a new world." The family had two branches - the Rougons were small shopkeepers and petty bourgeois, and the Marquarts were poachers and smugglers who had problems with alcohol. Some members of the family would rise during the story to the highest levels of the society, some would fall as victims of social evils and heredity. Zola presented the idea to his publisher in 1868. "The Rougon-Macquart - the group, the family, whom I propose to study - has as its prime characteristic the overflow of appetite, the broad upthrust of our age, which flings itself into enjoyments. Physiologically the members of this family are the slow working-out of accidents to the blood and nervous system which occur in a race after a first organic lesion, according to the environment determining in each of the individuals of this race sentiments, desires, passions, all the natural and instinctive human manifestations whose products take on the conventional names of virtues and vices."

At first the plan was limited to 10 books, but ultimately the series comprised 20 volumes, ranging in subject from the world of peasants and workers to the imperial court. Zola prepared his novels carefully. The result was a combination of precise documentation, dramatic imagination and accurate portrayals. Zola interviewed experts, wrote thick dossiers based on his research, made thoughtful portraits of his protagonists, and outlined the action of each chapter. He rode in the cab of a locomotive when he was preparing LA BÊTE HUMAINE (1890, The Beast in Man), and for Germinal he visited coal mines. This was something very different from Balzac's volcanic creative writing process, which produced La Comédie humaine, a social saga of nearly 100 novels. The Beast in Man was adapted for screen for the first time in 1938. The director, Jean Renoir wrote the screenplay with Zola's daughter, Denise Leblond-Zola. In the film Séverine (Simone Simon) wants her lover, the locomotive engineer Lantier (Jean Gabin), to kill her stationmaster husband. Lentier, an honest and proud man, cannot do it, but in a fit of anger and frustration he strangles his beloved instead and commits suicide by throwing himself off a fast moving train.

The appearance of L'ASSOMMOIR (Drunkard, 1877), a depiction of alcoholism, made Zola the best-known writer in France. He bought an estate at Médan and attracted imitators and disciples. Inspired by Claude Bernard's Introduction à la médecine expérimentale (1865) Zola tried to adjust scientific principles in the process of observing society and interpreting it in fiction. Thus a novelist, who gathers and analyzes documents and other material, becomes a part of the scientific research. He did not much believe in the possibility of individual freedom but emphasized the importance of external influences on human development. His treatise, LE ROMAN EXPÉRIMENTAL (1880), manifested the author's faith in science and acceptance of scientific determinism.

In 1885 Zola published one of his finest works, GERMINAL. It was the first major work on a strike, based on his research notes on labor conditions in the coal mines. The book was attacked by right-wing political groups as a call to revolution. NANA (1880), another famous work of the author, took the reader to the world of sexual exploitation. Zola's tetralogy, LES QUATRE EVANGILES, which started with FÉCONDITÉ (1899), was left unfinished.

Also notable in Zola's career was his involvement in the Dreyfus affair with his open letter J'ACCUSE. "In making these accusations, I am fully aware that my action comes under Articles 30 and 31 of the law of 29 July 1881 on the press, which makes libel a punishable offence," Zola wrote challenging. Alfred Dreyfus (1859-1935) was a French Jewish army officer, who was falsely charged with giving military secrets to the Germans. He was transported to Devil's Island in French Guiana. The case was tried again in 1899 and he was found first guilty and pardoned, but later the verdict was reversed. "The truth is on the march, and nothing shall stop it," Zola announced, but during the process he was sentenced in 1898 to imprisonment and removed from the roll of the Legion of Honor. He escaped to England, and returned after Dreyfus had been cleared.

Zola died on September 28, in 1902, under mysterious circumstances, overcome by carbon monoxide fumes in his sleep. According to some speculations, Zola's enemies blocked the chimney of his apartment, causing poisonous fumes to build up and kill him. At Zola's funeral Anatole France declared, "He was a moment of the human conscience." In 1908 Zola's remains were transported to the Panthéon. Naturalism as a literary movement fell out of favor after Zola's death, but his integrity had a profound influence on such writers as Theodore Dreiser, August Strindberg and Emilia Pardo-Bazan.